A Gentle Beginning

Most of us have grown up hearing that Lord Ganesha loves modak. We see it placed lovingly before Him during Ganesh Chaturthi, offered in temples, and prepared in homes with quiet care. And yet, a gentle question arises—what makes this simple, steamed sweet so dear to the Divine? Ukadiche Modak is not rich or elaborate. It is made of humble ingredients—rice flour, jaggery, and coconut—shriphal, the sacred fruit that naturally finds its place in offerings. It is a bhog that can be prepared by any household, without distinction of means or status. Perhaps that is its quiet beauty. When offered with patience and devotion, this modest modak becomes an expression of love, wisdom, and surrender. In understanding its place in worship, we begin to glimpse something deeper about bhakti itself.

Why Lord Ganesha Loves Modak

The affection of Lord Ganesha for modak is not merely a fondness for sweetness. In the stories associated with Him, modak quietly appears as a response to inner attitude—to humility, wisdom, and right understanding.

The Story of Kubera and Ganesha — When Abundance Was Not Enough

Kubera, the celestial treasurer, once invited Lord Ganesha to a magnificent feast, certain that wealth and abundance would please the Divine. Dish after dish was served, yet Ganesha continued to eat, and still His hunger was not appeased. Slowly, Kubera’s confidence gave way to anxiety, and pride dissolved into complete helplessness. Unable to understand how to satisfy the Lord, Kubera finally stood before Lord Shiva with folded hands, his riches rendered meaningless.

Seeing his surrender, Lord Shiva smiled. With quiet compassion, He handed a small modak to Kubera for Ganesha. prepared with love and devotion by Mother Parvati. Initially bewildered but with total humility accepted it. Lord Ganesha accepted it and put it in His mouth. That simple modak satiated the Lord’s hunger. He was content.

In this Lord Ganesh’s gentle exchange lies a profound truth. What abundance could not achieve, a mother’s love and a devotee’s surrender accomplished effortlessly. The modak was not special because of its form, but because it carried affection, humility, and pure intent. In that simplicity, the Divine was satisfied.

The Circumambulation of Parents — Humility Over Pride

A moment of comparison once arose between the two divine brothers—Kartikeya and Lord Ganesha—each confident of their own greatness. Sensing this, their parents intervened, declaring that whoever would circumambulate the entire cosmos first would be acknowledged as the greater of the two.

Kartikeya, filled with strength and confidence, immediately mounted his peacock and set off across the vast universe, determined to prove his superiority through speed and effort. Ganesha, however, paused. With folded hands and a calm heart, He simply walked around His parents, Shiva and Parvati, and declared them to be the cosmos itself—the source, the sustainer, and the center of all existence.

Pleased by this humility and insight, Shiva and Parvati embraced Him and offered Him the modak. The sweetness He received was not for winning a race, but for understanding where true greatness lies.

A Quiet Common Thread (Revised)

In these stories, modak appears not at moments of display or achievement, but at moments of surrender, humility, and right vision. Kartikeya’s pride carried him across the universe, yet it was Ganesha’s simplicity that brought Him home. Where ego seeks distance, devotion discovers closeness. And it is in this inward turning—marked by humility rather than pride—that the sweetness of divine grace is finally received.

Ukadiche Modak as Bhog for Lord Vishnu

In the Vaishnava understanding, bhog is offered not to satisfy hunger, but to honor sattva, purity of intent, restraint in action, and remembrance of the Divine as the sustainer of all. What pleases Lord Vishnu is not richness or display, but harmony—between ingredients and intention, effort and surrender. In this light, Ukadiche Modak finds a natural place as bhog.

Steamed rather than fried, simple rather than elaborate, the modak reflects the quiet qualities associated with preservation and balance. Its preparation avoids excess, its taste is gentle, and its form contains qualities that resonate with the spirit of Vaishnava worship. Made without agitation or indulgence, it aligns easily with days of restraint and prayer, and with offerings prepared to keep the mind calm and the heart steady.

There is also a subtle unity here. Lord Ganesha removes obstacles; Lord Vishnu sustains dharma. When a bhog like Ukadiche Modak is offered with humility, it carries both intentions at once clearing the inner path and nourishing the resolve to walk it rightly. The same simple offering thus becomes a bridge between beginnings and continuity, between grace that opens the way and grace that preserves it.

In temples and homes alike, such bhog reminds the devotee that devotion does not need complexity to be complete. When food is prepared with purity, offered with remembrance, and received as prasadam, it fulfills its highest purpose—not by impressing the senses, but by settling the heart into gratitude and trust.

From Food to Bhog

In everyday life, food is something we prepare to satisfy hunger, nourish the body, or please the senses. But in a devotional home or temple space, food gently transforms into something more—it becomes bhog. Bhog is not meant to feed God; it is meant to express love. The act of offering reminds us that whatever we prepare, whatever we possess, and whatever we enjoy ultimately belongs to the Divine.

This simple shift—from food to bhog—changes the way we cook and the way we serve. The kitchen becomes quieter. Movements become slower. There is less concern about impressing, and more attention on intention. In that sacred pause, cooking itself begins to resemble prayer. Ukadiche Modak belongs naturally in this space—not as a festive sweet alone, but as an offering shaped by humility and devotion.

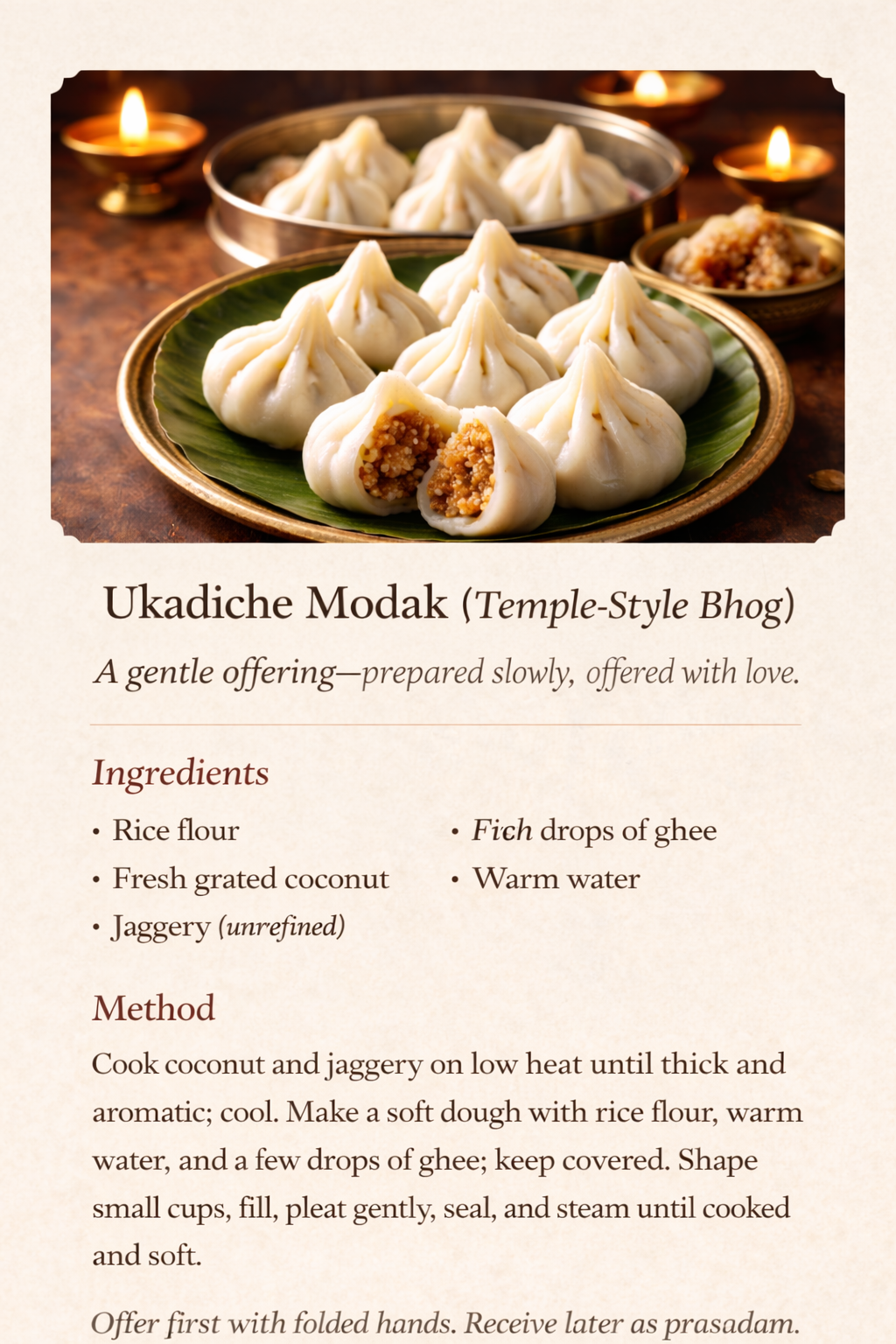

What Is Ukadiche Modak?

Ukadiche Modak is a traditional steamed offering, deeply rooted in devotional practice. The word ukadiche means “steamed,” and modak refers to a closed, sweet dumpling—simple in form, restrained in appearance, and gentle in taste. Unlike elaborate sweets meant for indulgence, this modak carries an unmistakable sense of humility.

Its ingredients are modest and familiar—rice flour, jaggery, coconut—items found easily in many homes, requiring no luxury or excess. Perhaps this is why Ukadiche Modak has remained timeless. It does not rely on wealth to convey devotion. Its closed shape, its softness, and its simplicity quietly reflect the inward nature of bhakti itself, where sweetness is not displayed outwardly but held within.

Prepared traditionally as bhog, Ukadiche Modak reminds us that what is offered with purity of heart carries greater value than what is offered with complexity or pride.

Cooking as Seva, Not Skill

When Ukadiche Modak is prepared as bhog, the focus naturally shifts away from skill and toward seva. There is no urgency here, no competition with time or perfection. The rice flour dough is brought together slowly, just warm enough to be pliable, requiring gentle hands and steady attention. The coconut and jaggery are cooked patiently, stirred until they soften into harmony, releasing a quiet sweetness that fills the space.

Often, a soft bhajan plays in the background—not to be listened to, but to be felt. Its gentle rhythm settles the mind, guiding the hands to move with care rather than haste. Each modak is shaped while the dough is still warm, the pleats formed one by one—not rushed, not forced. Some pleats may be uneven, some modaks less symmetrical than others, but that is not the concern. What matters is the calm with which they are shaped.

The modak is closed carefully, sealed with intention rather than pressure, and placed gently for steaming. As the steam rises, the kitchen grows quieter. There is nothing more to do but wait. No stirring. No checking. Only stillness, with bhakti resting softly in the atmosphere and in the heart.

In this waiting, something subtle unfolds. Patience is practiced. Attention deepens. The act of cooking becomes an offering. Without announcing it, Ukadiche Modak teaches that devotion is formed not through mastery, but through steadiness. What emerges from the steam is not just bhog, but a quiet reminder—that when actions are performed with love and restraint, they naturally mature into worship.

When Ukadiche Modak Is Traditionally Offered

Ukadiche Modak is not tied to a single moment; it appears naturally at times when devotion seeks simplicity and sincerity. Most familiarly, it is offered during Ganesh Chaturthi, when hearts turn toward beginnings, obstacle-removal, and inward alignment. On Sankashti Chaturthi, too, modak finds its place—offered after restraint, prayer, and quiet waiting,echoing the very patience with which it is prepared.

In many homes and temples, modak is also offered during special pujas and sacred observances, particularly on days that emphasize sattva,(purity) and remembrance. Its steamed nature and gentle sweetness allow it to align easily with worship that values restraint overindulgence. Whether during a festival or a modest home offering, modak carries the same meaning—it marks a moment when devotion chooses humility over display.

What remains constant is not the calendar, but the intention. Whenever prayer turns sincere and the heart seeks closeness rather than recognition, Ukadiche Modak feels at home on the altar.

Symbolism Hidden in Simplicity

(Ingredients and Form)

Ukadiche Modak carries its meaning quietly. Nothing about it calls for attention, and yet everything about it points inward. The symbolism it holds is not announced through ornamentation or abundance but revealed through restraint and balance, much like the path of bhakti itself.

The outer covering, made of rice flour, speaks of simplicity and sustenance. Rice has long been a staple of daily life, grounding the body and steadying the mind. As the outer shell of the modak, it represents discipline—the structure that holds devotion in place. It is plain, unadorned, and essential, reminding us that spiritual life too rests on simple, consistent foundations.

Within this modest exterior rests the sweetness of coconut and jaggery. Coconut, traditionally regarded as shriphal, finds its way into offerings not through explanation, but through familiarity and reverence. Jaggery, unrefined and gentle, brings sweetness without excess. Together, they suggest that true joy in devotion is natural and nourishing, not sharp or overstated. The sweetness is enclosed, not exposed—hinting that inner fulfillment is discovered quietly, not displayed outwardly.

The form of the modak completes this symbolism. Its closed shape gathers attention inward, while the pleats draw upward, as if guiding scattered energies toward a single point. Nothing spills out; nothing demands notice. The sweetness is protected, earned, and revealed only when the offering is received. In this way, the modak mirrors the inner journey of bhakti—where restraint gives rise to depth, and patience gives way to grace.

Even the act of steaming reinforces this message. Heat is applied gently, without direct contact, allowing the modak to mature without disturbance. There is no forcing, no haste—only steady transformation. What emerges is soft yet whole, shaped by care rather than control.In Ukadiche Modak, simplicity is not a lack—it is the very language through which devotion speaks.

Teaching Children Through Modak

Ukadiche Modak has a quiet way of teaching, especially to children—without instruction or correction. In its preparation, little hands learn to slow down. Pleats cannot be rushed; dough must be handled gently; waiting becomes unavoidable. Through this simple act, patience is practiced without being named.

As stories of Lord Ganesha are shared alongside the making, children begin to associate sweetness not merely with taste, but with values—humility, respect, and devotion. They learn that offering should be placed before the Divine before it is enjoyed, and that waiting transforms desire into gratitude. In this way, prasadam becomes more than food; it becomes understanding.

The modak does not lecture. It teaches by doing. By shaping it, offering it, and finally receiving it, children absorb a lesson that remains long after the sweetness fades—that joy deepens when it is preceded by care, restraint, and love.

Closing Reflection

In the end, Ukadiche Modak leaves us not with fullness, but with quiet understanding. Its sweetness is hidden, revealed only after patience, after waiting, after the offering is made without claim. Nothing is hurried—neither the shaping, nor the steaming, nor the receiving. In that gentle pause, surrender becomes natural. We learn that devotion does not demand grand gestures, only a willing heart that knows how to wait, how to offer, and how to trust. Like the modak itself, bhakti matures in stillness, holding its sweetness within, until grace chooses the moment to unfold.

🌼 Spiritual Significance (Inspired by Swami Mukundananda)

Swami Mukundananda often emphasizes that God does not hunger for food, but for love. When we prepare bhog with a selfless heart and remembrance of God, the offering becomes spiritually uplifting.

“The purity of devotion with which an offering is made is far more important than the offering itself.” — Essence of Swami Mukundananda’s teachings

Ukadiche Modak beautifully reflects this idea:

- Steaming (ukad) symbolizes humility and simplicity

- Sweet filling represents divine bliss

- Hand-crafted pleats reflect patience and loving effort

When prepared mindfully, the modak becomes a medium of bhakti (devotion) rather than just food.

Key Takeaways

- Bhog is love made visible. When we offer, we are not feeding the Divine—we are training the heart to remember who sustains us all.

- Simplicity carries its own sanctity. Ukadiche Modak teaches that devotion does not require luxury; it only requires sincerity.

- Humility is the sweetness God accepts. In Ganesha’s stories, the modak arrives when pride dissolves and surrender become real.

- Patience is a form of prayer. Pleats, steaming, waiting, each becomes a quiet spiritual practice when done with bhav.

- The sweetness is meant to remain within. Like the modak’s filling, bhakti matures inwardly unannounced, protected, and deep.

- Bhakti is for every home. A modak offering reminds us that grace does not recognize status—only the sincerity with which which we approach.

Frequently Asked Questions:-

1) What is Ukadiche Modak?

Ukadiche Modak is a traditional steamed rice-flour dumpling filled with coconut and jaggery, commonly offered as bhog—especially to Lord Ganesha.

2) Why is modak so closely associated with Lord Ganesha?

Tradition remembers Lord Ganesha as Modakapriya (one who loves modak), and stories around Him use modak as a symbol of humility, wisdom, and grace.

3) Why is coconut called shriphal?

Coconut is often called shriphal (sacred/divine fruit) in Hindu ritual contexts and is widely used in offerings.

4) Can Ukadiche Modak be offered to Lord Vishnu?

Yes—when prepared and offered as sattvic bhog, its simplicity and restraint align naturally with devotional offerings centered on purity and remembrance.

5) What if my modaks don’t look perfect?

Bhog is accepted by the Divine through bhav, not appearance. If the offering is prepared with cleanliness, patience, and love, its purpose is fulfilled.

Call to Action

If this reflection moved you, consider making Ukadiche Modak once—not as a culinary project, but as a quiet act of devotion. Play soft bhajan, let the kitchen become calm, and offer what you make with folded hands. Even one sincere offering can soften the heart.